MARYROSE COBARRUBIAS MENDOZA

June 3 - July 10

Maryrose Cobarrubias Mendoza

POP’d

June 3 - July 10

Exhibition Statement

POP’d surveys art created between 2010 - 2021. A mini introduction, a little retrospective of sorts––but make it POP!

Maryrose Cobarrubias Mendoza’s work is frequently framed around her identity as a Filipino American. While still honoring and celebrating the inextricable link between identity and artistic expression, From Typhoon presents, for the first time, a body of work that highlights the influence of Pop Art and Fluxus.

Pop Art was accessible to everyone and blurred the lines of high and low culture. In Fluxus, the importance of moments and awareness was key. Both of these art movements were also formative because of their anti-institutional roots and spoke to Mendoza as a young artist not seeing herself reflected in the art world.

For the last several years, Mendoza has been working with challenging subject matter influenced by the 2016 election, the ensuing social climate, and the American public education system. Throughout her career she has always been drawn to ideas and aesthetics that elevate the everyday and celebrate the common object. Since these notions continue to inform her practice even as it has evolved into more direct social and political exchange, we are excited to see older and newer works together in the same space.

For sales & general inquires: info@fromtyphoon.com

Installation Shot: Trunk III & Trunk IV

Installation Shot: Trunk III & IV, raft, Sio Pao (bun), Son, & Kayumanggi

Installation Shot: Isla, Trunk III & IV, Kayumanggi, Crayon label drawing, Sio Pao (box), & Paper

Installation Shot: Photo

Photo, 2015

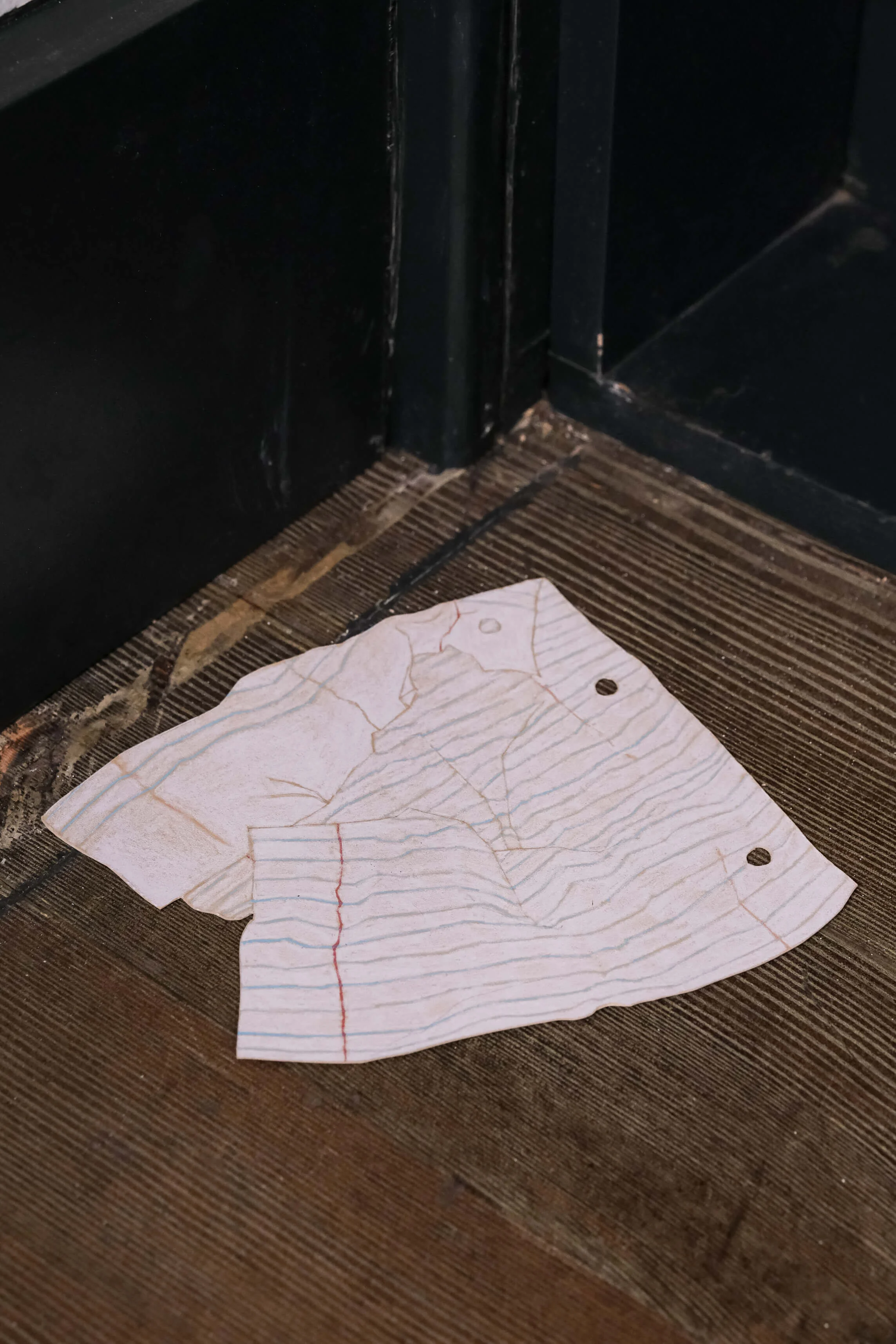

Installation Shot: Paper

Paper, 2015

Installation Shot: Ruled Flag, Happiness Is a Warm Gun, Hi. It's been awhile, & Soldier Series

Installation Shot: raft, Open, & storage

Installation Shot: Kayumanggi & Son

Son, 2021

Kraft Paper, ink, adhesive, paper, wire

73 x 42 x 24 1/2 in

Price upon request

Having incorporated the brown paper bag in previous works of art, Mendoza believes its undeniable familiarity and aesthetics recall immediate associations of memory and childhood. Son taps into the social construct of the school lunch and the way each viewer interprets how the bag’s elements convey stratification of class, race, and culture.

1587, 2021

Shrinky Dinks plastic, colored pencil

4 1/4 x 3 1/2 in

800

The year 1587 refers to the first documented landing of Indigenous Filipinos in North America, at what would become Morro Bay, California. Mendoza created this drawing during Asian American Pacific Islander Month to mark the significance of how long Filipinos have been in the Americas. She created a yellow piece of ruled line paper to convey the marking of data or the beginning of a log of the countless numbers of immigrants from Asian countries who have arrived since. The yellow coloring also relates to legal paper and the notion of race.

Ruled Flag, 2010

Shrinky Dinks plastic, colored pencil

28 x 44 x 2 in (framed)

4800

Created for Mendoza’s 2010 solo exhibition, “Omitted,” this piece relates to the awareness of how the histories of generations of “others” outside of the dominant culture were not taught about, and therefore never seen, heard, or considered. 50 sheets of blank ruled line paper representing the 50 states address that “invisibility” of language, story, and representation in the American educational system.

Happiness Is a Warm Gun, 2017

Felt, air guns

39 x 27 1/2 x 2 1/4 in (dimensions variable)

2500

Borrowing its title from the Beatles’ song, this piece arrays various guns into a form that could not possibly be used safely to address the sheer number of guns many Americans feel they need or want. Real air guns wrapped in felt reference the artist Joseph Beuys, who used felt in his work to create a mythology around his persona. Mendoza, having grown up in the seventies, also acknowledges her memories of the iconic silhouette from the Charlie’s Angels television series.

Kayumanggi, 2019

plastic, wood, paper, colored pencil

59 x 6 in (diam)

(with plinth)

5000

Kayumanggi, simply translated from Tagalog to English, is the color brown. However, the usage of the word has untranslatable connotations. It’s the color of skin heated under the Pacific sun, steamed by tropical humidity, and cooled by sea breezes. Kayumanggi is brown love. Kayumanggi is Filipino pride. The other crayon in past exhibitions, Growing up Brown, refers to a generic way to describe and group people racially and ethnically. Here, Kayumanggi not only specifies language and location, but becomes a source of pride in skin color and cultural values.

terrace, 2018

found cardboard boxes

5 x 10 ft

(dimensions variable)

SOLD

The rice terraces of the Philippines are the inspiration for this wall piece made entirely of found cardboard boxes. The boxes are identified by products made in many countries including the United States, the Philippines, and China.

This work references Rice Terraces of the Philippine Cordilleras (a UNESCO World Heritage Site) that were carved in the mountainsides by indigenous peoples and are still today used for cultivating rice. In her work terrace, Mendoza uses industrial packaging in a terraced format as a metaphor for the way labor has shifted from farming to mass production in her native country. The boxes also refer to the problem of industrial waste, which has become an ecological disaster in the Philippines, creating masses of garbage like the “Smokey Mountain” area outside of Manila.

raft, 2018

Paper, gouache, cardboard, spray paint

pallet: 5 x 36 x 36 in; bags: 3 @ 24 x 15 x 5 in (each)

Price upon request

In this actual-size scaled sculpture, the “rice bags” and “pallet” refer to cross-cultural exchange, as in trade, commerce, immigration, migration, consumerism, and globalism. The logo and text is appropriated and inspired from the Botan Rice brand that was the familiar, go-to rice, for many Asian immigrants in the 1970’s in California. Responding to the graphics, Mendoza playfully used a lotus flower instead of the original rose motif and changed the company name to “Baton,” to loosely sound like Bataan–as in Bataan Death March–or a baton that is passed on in a relay.

Open, 2015

Paper, colored Pencil

18 x 19 inches (dimensions variable)

(framed)

2800

First shown at Mendoza’s 2015 solo exhibition, “This Must be the Place” at Commonwealth and Council, Open counters Western linear perspective by using an isometric perspective. While the pink pastry box was first a reference to the Chinese pastries of her youth, in this drawing, Mendoza is remembering her high-school job at Rainbow donuts, the open, empty box conveying a passing of time or what once existed there.

storage, 2019

pastry boxes (hand-cut and folded)

32 x 17 x 9 inches

(with artist’s cardboard box pedestal)

4500

Since 2006, Mendoza has incorporated the image of the pink box—the ubiquitous, ready-made object associated with Southern California donut shops that for Mendoza has emotional connection to childhood bakery visits on Chinatown’s New High Street. The pagoda form is inspired by her visit to Japan.

Isla, 2020

pastry box, scenery materials, acrylic, found trash

13-1/2 x 9 x 13-1/2 in

3000

The pink pastry box has become an avatar for Mendoza, alluding to her identity as a Filipina and Asian American. In Isla Mendoza packages as a curious treat a tropical island with coconut trees and a lush jungle landscape amidst a dark sea. The pink pastry box symbolizes the packaging of culture in sterilized and/or standardized ways. Like the immigrant experience of feeling both belonging and otherness, the box expresses familiarity while the contents express difference.

Trunk III, Inappropriation, 2018

Paper, colored pencil

24 x 32 in

(framed)

4500

‘Trunk III' is the third drawing in a series of truncated images that are drawn and eventually hung to emulate Mendoza’s visual point of view. The drawing explores identity, heritage and stigmas through the appropriation and interpretation of indigenous Kalinga tribal tattoos from the Philippines.

Crayon label drawing, 2019

Paper, colored pencil

(framed)

4000

For the original colored pencil drawing created for the Kayumanggi crayon sculpture, Mendoza layered various shades of brown to emulate a kind of skin for the crayon.

The motifs on the left and right sides of the label reference both the original Crayola crayon design as well as indigenous tattoo art of the Philippines.

BIO

Through replication, scale, and perspective, Maryrose Cobarrubias Mendoza uses personal touch and common materials to transform the banal via drawing, sculpture, and installation toward visual poetry. Creating a visual language inspired by “things” helps restore parts of spoken language that were often absent or confusing during Mendoza’s childhood, since neither her native nor non-native languages were fully formed when she immigrated. From the spaces between American, Filipino, and Filipino American cultures, Mendoza investigates colonized and decolonized perspectives reflecting circumstances of cultural amnesia and assimilation through the process of the handmade.

Mendoza’s work was most recently exhibited as part of the Orange County Museum of Art OCMAExpand series. She has also exhibited at the Pacific Asia Museum, the Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery, the Armory Center for the Arts, PlugIn Gallery, SOMA Arts, YYZ Artist Outlet, Commonwealth and Council, and many others.

Mendoza’s work has been featured in publications including Asian Pacific Sculpture News, the Nomadic Journal, the Globe and Mail, Artweek, and City Beat, among others. She is a recipient of a 2019 Guggenheim Fellowship, a COLA Individual Artist Fellowship, a NY Art Matters Fellowship, and others. She has participated in Artist-in-Residence programs at Yaddo Artist Residency, Joshua Tree Highlands Residency and Art Space Yosuga in Kyoto.

Maryrose was born in Manila, Philippines, and immigrated to the United States at the age of three. She lives and works in Los Angeles County where she is an Associate Professor and Drawing Coordinator at Pasadena City College.

For sales & general inquires: info@fromtyphoon.com